“The eternal silence of these infinite spaces fills me with dread.” Pascal

Foreword by Dr. Rupesh Agarwal, M.D., chief physician of the NASA medical team.

Insomnia during space travel is not uncommon, and is usually a transient symptom of the disruption of circadian rhythms. The four astronauts aboard the Aeolus, the first manned mission to Mars, all reported difficulty sleeping during the nine-month voyage out. As they neared the Red Planet, a meteor shower left the landing module damaged beyond repair. Their only choice was to maintain orbit for the three months it would take for Earth and Mars to be in Close Approach (their nearest distance apart, about 34 million miles) for the nine-month elliptical path home.

It was soon after the ship departed for Earth that all four astronauts experienced chronic insomnia that proved intractable without medication. Dr. Elise Lindfors, the ship’s physician and science officer, sent regular, detailed reports on the medical condition of the crew: Captain Augustus Wren, Lieutenant Zhin-Yi Liu, ship’s engineer, and Major Tove Heimdal, pilot and navigator, and we are deeply indebted to her, for it is only through these written transmissions selected from the return voyage that we have been given the partial picture we have of the series of events resulting in the tragic loss of the Aeolus. It is impossible to know how accurate Dr. Lindfors’ reports were, especially near the end, as she was suffering from the same anomalous symptoms afflicting the rest of the crew, but it is all we have, and will remain both an invaluable historical record and a cautionary tale for the future of manned space travel.

Day 385: Capt. Wren has the most deep space experience among us, yet he has never traveled farther than about 1.2 million miles from Earth, on an exploratory mining mission five years ago to Asteroid 7482. No human beings have ever journeyed this far from Earth. Our training for the mission was rigorous and exhaustive. We were prepared to expect loneliness, homesickness, and the inevitable conflicts that occur when four people are confined in a limited space for almost two years. The main module’s centrifugal spin keeps us just slightly under Earth gravity, and we have continued the series of daily exercises designed to limit the expected loss of bone and muscle mass. There were no significant physical complaints besides minor episodes of vertigo and dyspepsia, until Day 51, when Major Heimdal reported problems sleeping.

The symptoms, which quite soon all of us shared, were unsettling: a formless anxiety expressing itself as nervous energy, that no amount of exercise could overcome, and a disturbed feeling in the solar plexus that seemed to short-circuit the possibility of drowsiness and persisted until we all needed medication to get our minimum six hours of sleep.

For several weeks the medications allowed us to function more or less normally, and although I knew that nightly use of benzodiazepines and/or zolpidem would eventually result in drug resistance and dependence, it seemed preferable to the alternative. Captain Wren agreed with me. The insomnia was worrisome but manageable during the voyage out, although it mitigated to some degree during our long orbit of Mars. This may have been due to our close proximity to a planetary body, the natural home of all life forms we know of, even one so inhospitable to human life.

Our sleeplessness has noticeably worsened since departing for Earth. Eight more months of travel await us, and I am deeply concerned. Physically and psychologically, we are not a healthy crew.

Day 397: The etiology of our insomnia has so far eluded me. I’ve considered every possible cause, from the body’s inability to adjust to the loss of circadian rhythms, to the possibility of a microbe unknowingly brought with us from Earth mutated by cosmic radiation into something that is altering or destroying GABA and other sleep-inducing neurotransmitters. My shot-in-the-dark hypothesis is that leaving Earth’s orbit for a certain length of time may have a profound, and ultimately fatal, effect on all terrestrial organisms more complex than tardigrades, those strange aquatic creatures the size of a period at the end of a sentence, that can live for an indefinite time even in the vacuum of space. We may be intimately tied to Earth in ways we never imagined, and after leaving behind the electromagnetic fields and manifold biochemical interactions of our home planet, we wither and die. The truth is, I don’t know why none of us can sleep without drugs, nor am I sure that we can survive the voyage home if the insomnia worsens. What I do know is, the human brain needs daily periods of regenerative slumber, not just chemically induced oblivion for short periods, and without it, body and mind deteriorate.

Day 442: Our supply of oral sleep meds is running low. I’ve suggested every alternative treatment in the book: intense exercise, chess and other complex games to tire the mind, puzzles, late-night reading, even hypnosis, but drugs are all that seem to work. Tove has developed such a strong resistance to the medications that he isn’t sleeping more than an hour a night, and it shows in his work and his behavior. He’s irritable and sometimes combative, if not insubordinate, and although able to fulfill his duties, he is showing the effects of profound exhaustion. Zhin-Yi, on the other hand, functions reasonably well during her work shifts but wanders the ship during her sleep periods, unable, she says, “even to close my eyes.” She does sleep, however fitfully, knocked out by Ambien for short periods, because I’ve checked on her at various times during the “night,” and found her sleeping. Captain Wren is doing his best to maintain his stoic captain face, but he, too, is slipping, and has admitted as much to me. If someone dozes off during a meal or while performing his duties, the captain has ordered us to let him sleep, but this rarely happens. Lately, when I’m reading, the letters seem to twist themselves into meaningless hieroglyphics, or crumble into dust, unmistakable signs of sleep deprivation psychosis. To come back to full alertness, I sometimes have to slap myself, hard. But when I try to sleep, my body becomes charged with a tingling energy that seems to actively resist the drugs. I pace my cabin for hours, waiting for the ever-larger doses of Valium to kick in. Sometimes I get two hours; other nights, thirty minutes. I’m making mistakes, forgetting words, having trouble concentrating.

Day 450: Is there a cause I’m overlooking? Or is it just Space itself, the madness of it, extending infinitely in all directions? And inside of us, too. We ourselves are universes, embedded like nesting dolls in the spreading aftermath of the Big Bang. Is the universe cyclical, an endless series of explosive births and slow-death contractions back to an infinitely dense particle? Is there any end to this eternal Somethingness? Useless questions. We’ll never know, or as Nietzsche suggested, we’ve always known, and will never remember that we’ve seen and done all this a billion times before.

On Earth we can only imagine this stupendous emptiness, shielded as we are by the fragile skin of the atmosphere, which even at night protects us from more than a partial awareness of Einstein’s ‘finite but unbounded universe.’ Like Mars, Earth is a pebble in eternity, but we don’t really feel it as such, with the solid ground under our feet, the clouds overhead, the noises, smells, colors, seasons—all the distractions of life and time.

Out here, the mind, or perhaps I mean the soul, is naked. I’ve become neurotically aware of my body’s fragility. A tardigrade (I’m starting to envy those tiny beasts) can survive under conditions that would destroy most creatures, because it can generate a sugar that preserves its cells, while expelling all the water from its body as it enters a dormant state, like a living mummy. It’s the next thing to an immortal being; just add water and it lives again. That’s the kind of body true space travelers would need. We humans—flimsy bags of modified seawater—are not built for this. Maybe in the future the human body can be adapted for life on other planets. But to somehow evolve for survival in the airless, absolute cold of deep space? No. This will never be our home. We don’t belong here.

Day 456: What I’m naming, for want of a better term, the Mirror Syndrome, began, for me, last night. There aren’t any nights on a spacecraft, of course, just periods of lights on and lights off that are supposed to match our body’s need for night and day. It had been a typically awful sleep, a fitful, dreamless hour or two at most, and I got up to take another Valium. The bathroom is my cabin is about six by six feet, with a small mirror over a tiny sink and a chemical toilet that recycles urine and composts feces to be used as fertilizer in the greenhouse.

As I fumbled in the dark for a Valium, the bottle slipped from my hands and spilled its contents on the floor. I turned on the light, and when my eyes had adjusted I recovered the precious pills and put them back in the bottle, then stood up to secure the bottle in the rack. Knowing how haggard my face has been looking for weeks now, I at first merely glanced at my reflection. Then I looked again, and for a long time just stood there, unnerved, meeting the gaze of the stranger staring back at me. It was my face in the mirror, mine in every detail, the mole in the right fold of my nose, the coarser gray hairs sticking up from the part in my brown hair, my straight, thin lips and puffy eyes—and yet it wasn’t. Not exactly. It was more like an aspect or double of me than a reflection, some split-off fragment inhabiting the depths of the mirror.

I’m not expressing this well. I don’t mean to imply that it wasn’t my reflection, because it was. Yet it seemed more hallucinated than real, evoking the eerie feeling one gets looking into a mirror while dreaming, knowing that some hideous transformation is imminent. Naturally, I linked this experience to prolonged sleep deprivation, compounded by too much Valium. But I was badly frightened, and worried, because I knew that if it was happening to me, there was a good chance it was happening to my shipmates as well. How much longer can we go on like this?

Day 462: Over the last several days, all four of us have experienced the same symptoms. Captain Wren and Major Heimdal have stopped shaving, so disturbing have their reflections become to them, and Zhin-Yi and I have begun applying what little make-up we wear without using a mirror. The months of insomnia and nightly use of hypnotic drugs have been responsible for a steady disruption of REM sleep, which I know, from the sleep deprivation studies I did years ago at Hopkins, will eventually result in—if it hasn’t already—literally dreaming awake, complete with paranoid behavior. And yet, instead of surrendering to sleep as if to an overwhelming force, as we should be, our brains seem to be treating it like an enemy. We are waking up multiple times at night to take more pills. What bothers me is the sameness of our symptoms. On Earth, the content of hallucinations in psychotic episodes are always unique to the sufferer. But on this ship, we’re all having the same nightmare.

The neurotransmitters involved in the process of falling asleep—gamma aminobutyric acid, or GABA, adenosine, melatonin, nitric acid, all contribute to the brain’s normal need to flush out the chemicals of wakefulness: norepinephrine, epinephrine, cortisol, orexin and hypocretin that build up during waking hours. When the brain is in balance, one state follows the other without the stress factors that can lead to insomnia. One or all of the chemicals involved in producing the drowsiness that allows the brain to shut down its conscious side have been interrupted in the four of us. Could it be the melatonin, which is secreted by the pineal gland? The problem is, I have no way of testing these levels in a living brain.

Day 472: Captain Wren called a meeting this morning, during which he asked each crew member to describe his or her “internal weather.” All of us, I have to say, looked terrible: four unutterably weary, disheveled exiles from metabolic homeostasis, with thousand-yard stares and pickled-looking skin. We’d been avoiding each other for days, speaking as little, beyond the performance of our respective duties, as possible. “You needn’t fear having your sanity doubted,” he said. “I think we’re all experiencing the same, well, let’s say identity problems.” What emerged as we told our stories, was alarming. In just a few days since we first noticed the symptoms, the effects of the Mirror Syndrome have greatly worsened. We are beginning to see our own faces and bodies superimposed over those of our comrades. Tove, looking flinchingly but directly at Captain Wren, described it as a “holographic image of me occupying the same space as you, that’s slowly gaining more definition, while yours is getting dimmer.”

Zhin-Yi, who has an identical twin in London, reports being startled by the sight of her twin walking past her in the corridors, and she has to repress the urge to speak to her. In the last two days, she said, it’s looking less and less like her twin and more like her double. “I see four of me,” she said, peering strangely at each of us. “But I know that three of them are imposters.” I said that my own experience has been virtually the same, but trying to inject a humorous note, added that my hallucination doesn’t involve my other senses, so that when seated across from three more Elise Lindfors at the dinner table, I know they aren’t me because I don’t have a raspy baritone like Captain Wren, or a Norwegian accent like Tove Heimdal, and couldn’t fake Zhin-Yi’s engineer-speak if I tried. This evoked a chuckle or two, but I think we all know that we may soon have no markers besides our own internal thought processes to differentiate one another from ourselves.

Captain Wren asked me if I had any answers for “this space madness, or whatever it is.” I had to say no, but thought it likely that our prolonged insomnia was the first stage of what we were now experiencing. I refrained from voicing my fears that deep space itself might be the triggering factor, not some organism or unknown radiation. “The drugs are keeping us functional,” I added. “Which for the time being, outweighs the risks of addiction and psychosis.” “Will they get us back to Earth?” he asked. “At our present dosage levels, we’ll run out two months before entering Earth orbit,” I replied. “Thank you, doctor,” he said, calmly, then dismissed us. Bless the man! He’s trying to carry us all on his back.

Day 481: The doubling mirage has become fixed and indelible since my last entry, and the only person I now see on the ship is myself. I know that I’m a physician and a scientist, not an engineer, a captain, or a pilot. And my shipmates know the same thing, that we are separate individuals of different ages, sets of parents, personalities, past memories, abilities. We are members of a species with billions of individuals, each with his own unique face. Yet this illusion keeps forcing itself on our brains, making it increasingly difficult to remember that each of us is one fourth of a whole crew, not some bizarre quadruple being with a single identity. Such a strange thought: that each of us sees his or her own face and body. Only in that sense does our individuality persist, as if the genetic core of our physical being cannot be entirely effaced, and each perceives himself as both one and four. But we all have our own set of memories, too, our own persistent ego-self. Will that condition continue? How much longer before separateness becomes the illusion, before each of us begins to hear his or her own voice when another speaks to us, and accepts it as the reality?

Continue to Part 2 on May 5th

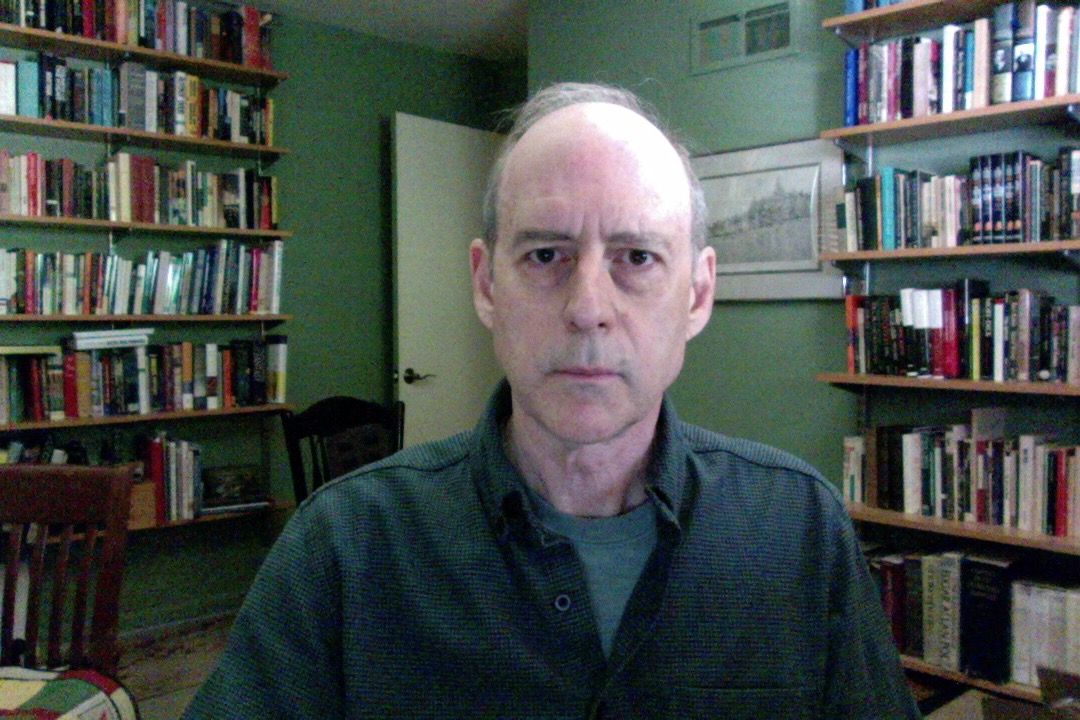

I was born in Michigan, grew up in Florida, and now live in Bethesda, Maryland. I’ve been writing and publishing mostly short stories and a few novellas since the 1980s. Twenty-five stories of mine can be found at Bewildering Stories.com, four on decomP Magazine, and three at Altered Reality.

I was born in Michigan, grew up in Florida, and now live in Bethesda, Maryland. I’ve been writing and publishing mostly short stories and a few novellas since the 1980s. Twenty-five stories of mine can be found at Bewildering Stories.com, four on decomP Magazine, and three at Altered Reality.

![]()