Merfolk: Sea People of Folklore and Legend

Richard H. Fay

Featured in the lore of many human cultures, merfolk were said to be people of the sea, although some resided in freshwater. In their most usual form, these beings appeared humanoid from the waist up and pisciform from the waist down. However, some chronicles and tales presented variations from this standard. At times hostile, at other times helpful, merfolk interacted with land-dwellers in various ways. Certain stories even spoke of marriages between merfolk and mortals, unions that could produce lines of human descendants. With potential links to ancient gods, goddesses, and monsters, merfolk have been a fixture of human legends for ages, but some accounts suggest that they are more than mere creatures of legend. Surprisingly enough, various historical records describe actual encounters with these aquatic entities, According to some reports, such encounters have even persisted to the present day.

The origins of merfolk lore might be as murky and difficult to plumb as the ocean depths themselves, but possible precursors to the merfolk of later chronicles and tales may be found in ancient myths and legends. Oannes, god of wisdom who granted the ancient Babylonians the gift of culture, appeared as a human-fish hybrid (Sykes & Kendall, 1993). The Philistine god Dagon and the Syrian goddess Atargatis were also depicted as prototypical merfolk (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). Mythographer Robert Graves traced a connection between mermaids and sea-born goddesses Aphrodite and Marian (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). The Greek scholars Nicholas Polites and Stilpon Kyriakides argued that the mermaid of modern Greek lore, the gorgona, shares features with the siren of Classical Greek myth (Simpson, 1987). Notwithstanding the fact that medieval authors did conflate the sailor-luring siren of ancient lore with the northern mermaid, Classical depictions portrayed the siren not as half-woman, half-fish, but as a monster that possessed a woman’s head and torso atop a bird’s body (Rose, 2000).

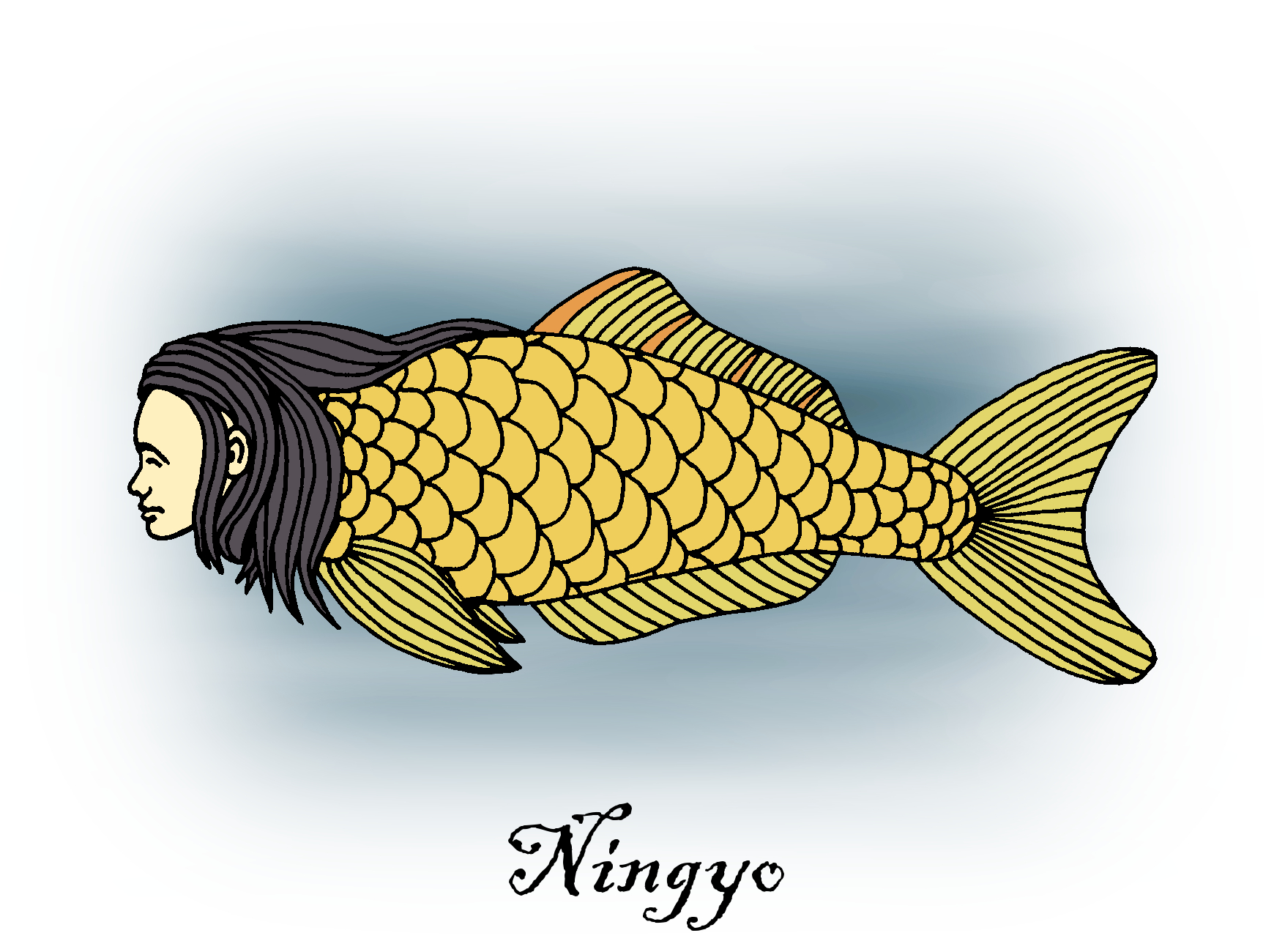

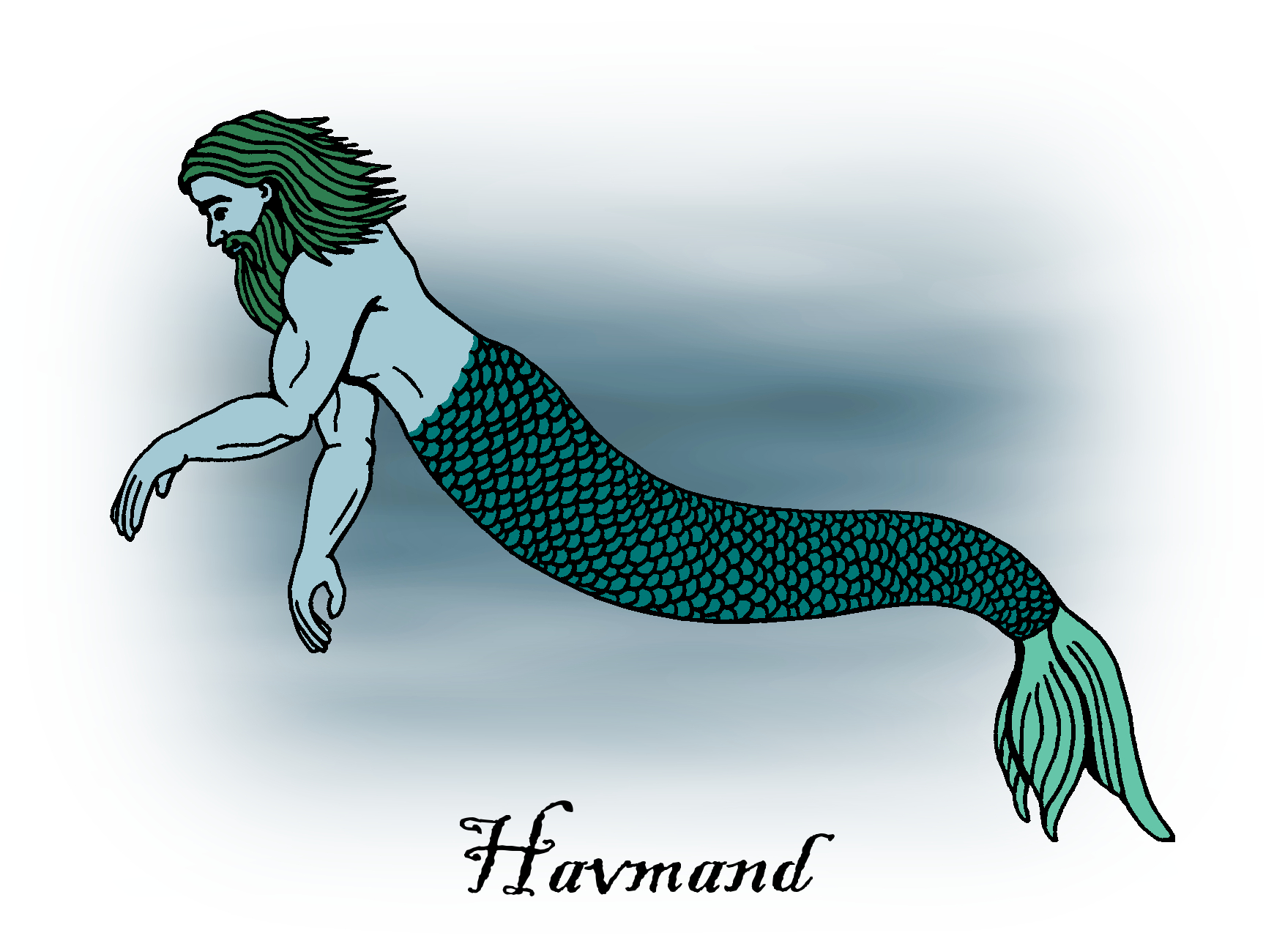

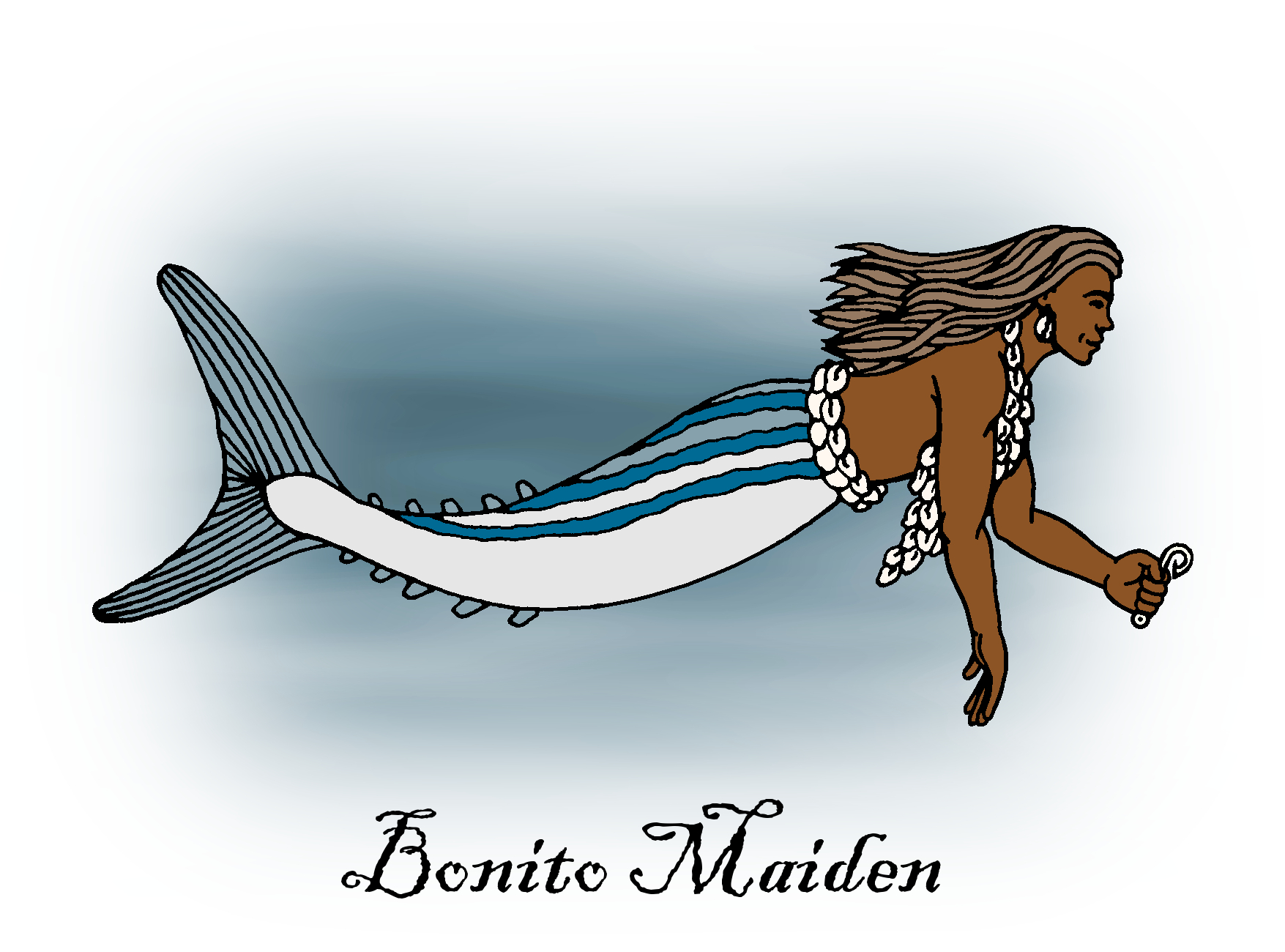

Although the true nature of alleged links between ancient gods and merfolk of later times may be doubtful, there is no doubt that such beings feature in folklore and legends around the world, from Ireland to New Ireland, New Guinea. The usually peaceful Irish merfolk known as merrows wore magical red caps that allowed them to shape-shift and travel back-and-forth between their undersea realm and dry land (Rose, 1996). The Manx mermaid ben varrey exhibited two conflicting natures, one a benevolent finder of treasure, the other a malevolent enchanter of men (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). The handsome Danish merman havmand treated those mortals he encountered with kindliness, while his female counterpart havfrue could be either helpful or harmful (Rose, 1996). Like the sirens of ancient myth, the alluring Swedish mermaids called sjörå entranced boatmen at sea and destroyed both mortals and their vessels (Marriott, 2006). The cannibalistic mermaids of Portuguese tales went one step further and devoured those lured into their watery abode (Marriott, 2006). The far more benevolent ningyo of Japanese lore brought peace and dispelled bad luck (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). Clad in cowrie-shell jewelry, the bonito maidens of the Solomon Islands acted as caretakers of both bonito fish and lost ivory fishing hooks (Rose, 1996). The singing ri of New Ireland tradition resided among the mangroves and along the strand (Rose, 2000). On the east coast of Canada, the halfway people of Micmac legends alerted courteous fishermen of impending storms (Rose, 2000).

Merfolk through the ages and across the globe have traditionally appeared as humanoids with fishy tails, exemplified by the beautiful-but-deadly comb-and-mirror-wielding sea maiden of the English folk song The Mermaid (Briggs, 1978), but there are variations to this tradition.

The 1st century author Pliny described mermaids as being completely scaly head-to-tail (Rosen, 2008). The medieval Irish Annals of the Four Masters told of a truly monstrous mermaid said to have measured a whopping 160 feet long (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). Another oversized mercreature featured in a report made to Bishop Pontoppidan of Bergen in 1719 that described a human-faced seal-like beast 28 feet long (Rose, 2000). Male merrows appeared downright hideous in aspect, possessing green-coloured hair, teeth, and skin, pointed red noses, and piggy eyes (Rose, 2000). On occasion, the Danish havmand was said to have had blue skin (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). Instead of looking like a human woman from the waist up, the Japanese ningyo could appear as a huge fish with a woman’s head (Rose, 2000).

Along with the varying physical descriptions of merfolk, different human cultures expressed different views regarding what merfolk symbolised. In medieval Europe, mermaids represented deceit and were believed to be in league with the Great Deceiver himself, the devil (Rose, 2000). Additionally, the medieval church considered mermaids to be symbols of vanity, lust, and the soul-endangering aspects of femininity and sex (Rosen, 2008). In Tudor times, the word “mermaid” became synonymous with the word “prostitute” (Franklin, 2002). Conversely, the Afro-Brazillian Batuque cult saw their aquatic jamaína and imanja as intermediaries between mortals and angels (Rose, 1996). The Japanese thought of their ningyo as a positive entity, a protector of the land (Matthews & Matthews, 2005).

As has been touched upon above, merfolk in various locales and circumstances sometimes dealt with land-dwelling mortals in a less-than-beneficial, or even outright malevolent, fashion. The otherwise friendly male merrow named Coomara captured the souls of drowned sailors in cages in the mistaken belief that he was performing a good deed sheltering the souls and keeping them warm and dry (Croker, 1882). Mermen of a more baleful nature were believed to conjure terrible storms and sink ships (Rose, 2000). At times, the female of the species also acted in a destructive manner; the subject of the folk song The Mermaid sent a ship of doomed souls to the bottom of the ocean (Briggs, 1978). The Norwegian havfine herded the waves and wrecked vessels foolish enough to be caught asea when storms rolled in (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). The Scottish lake-dwelling mermaid encountered by the youthful Laird of Lorntie proved to be a downright bloodthirsty creature that would have feasted on the young laird’s blood had his loyal servant not pulled him from the loch’s waters (Briggs, 1979).

Of course, not all merfolk treated humans poorly; some had favourable and even intimate dealings with humankind. According to Danish lore, a prophesying havfrue foresaw the birth of Christian IV of Denmark (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). In one Scottish story, a young man learned how to cure his ailing love with an infusion of mugwort when a mermaid surfaced and sang of using the herb to prevent the girl’s death by consumption (Briggs, 1978). A mermaid that rose from a Renfrewshire pool as a funeral procession crossed a stream advised the mourners how to use both mugwort and nettle to ward off fatal illness (Briggs, 1978). In the tale The Old Man of Cury, a stranded mermaid rescued by an old man granted her saviour the gift of healing (Briggs, 1978). The title mortal of Lutey and the Mermaid was rewarded with similar benefits when he aided a mermaid, but found himself lured into her watery abode nine years later (Briggs, 1978). Along with knowledge of healing herbs, rescued mermaids could also warn of impending storms (Rose, 1996). On occasion, female merrows wedded mortal men and gave rise to a line of human descendants who possessed webbed fingers and scaly legs (Briggs, 1979). A mermaid was said to number among the ancestors of the McVeagh clan of Scotland (Franklin, 2002).

Apart from marriages and other relations between merfolk and mortals, some stories told of humans transformed into sea people. According to a popular Greek legend, Alexander the Great‘s sister, Thessalonike, turned into a mermaid when, grief-stricken by the death of her conquering sibling, she attempted suicide by throwing herself into the Aegean Sea (DocumentaryMakedonia, 2013). Lí Ban, the pagan subject of a 12th or 13th century Irish tale, underwent a magical metamorphosis from human woman to mermaid after the majority of her kin were drowned in a flood (Ó hÓgáin, 2006). According to a certain Irish legend, pagan crones became mermaids when Saint Patrick expelled them from the land (Franklin, 2002). In the Samish story of Ko-kwal-alwoot, a maiden became enamoured with a merman who insisted on taking her as his bride and who eventually transformed her into a sea-dweller like himself (Matthews & Matthews, 2005).

Beyond the myths, legends, and folktales about merfolk told over the centuries by many different storytellers around the globe, sailors and fishermen across the ages have reported real-life sightings of fishy-tailed humanoids. Christopher Columbus wrote that he spied three less-than-lovely mermaids off the coast of what is now the Dominican Republic in January 1493 (Salaperäinen, 2016). In 1560, the bodies of several mermaids netted off the coast of Ceylon underwent dissection at the hands of a learned physician who concluded that, externally and internally, the anatomy of the merbeings resembled that of humans (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). Henry Hudson recorded that two of his crewmen spotted a white-skinned black-haired mermaid in 1608 (Cohen, 1982). In 1723, a Danish Royal Commission tasked with proving that merfolk existed only in myths and legends ended up running across an actual merman near the Faroe Isles (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). In 1830, residents of the isle of Benbecula in the Hebrides found the body of a small dark-haired white-skinned mermaid with “abnormally developed breasts”, perhaps the same creature that had been seen and injured at Sgeir na Duchadh a few days earlier, washed ashore at Culle Bay (Munro, 2016). Three years later, natural history professor Dr. Robert Hamilton described the capture of a short-haired monkey-faced mermaid offshore of Yell in the Shetland Isles (Munro, 2016). During a few notable summers around 1890, hundreds of eyewitnesses claimed to have seen the so-called Deerness Mermaid, a black-headed white-bodied creature that appeared like a human when swimming in the waters of Newark Bay, Orkney (Towrie, n.d.).

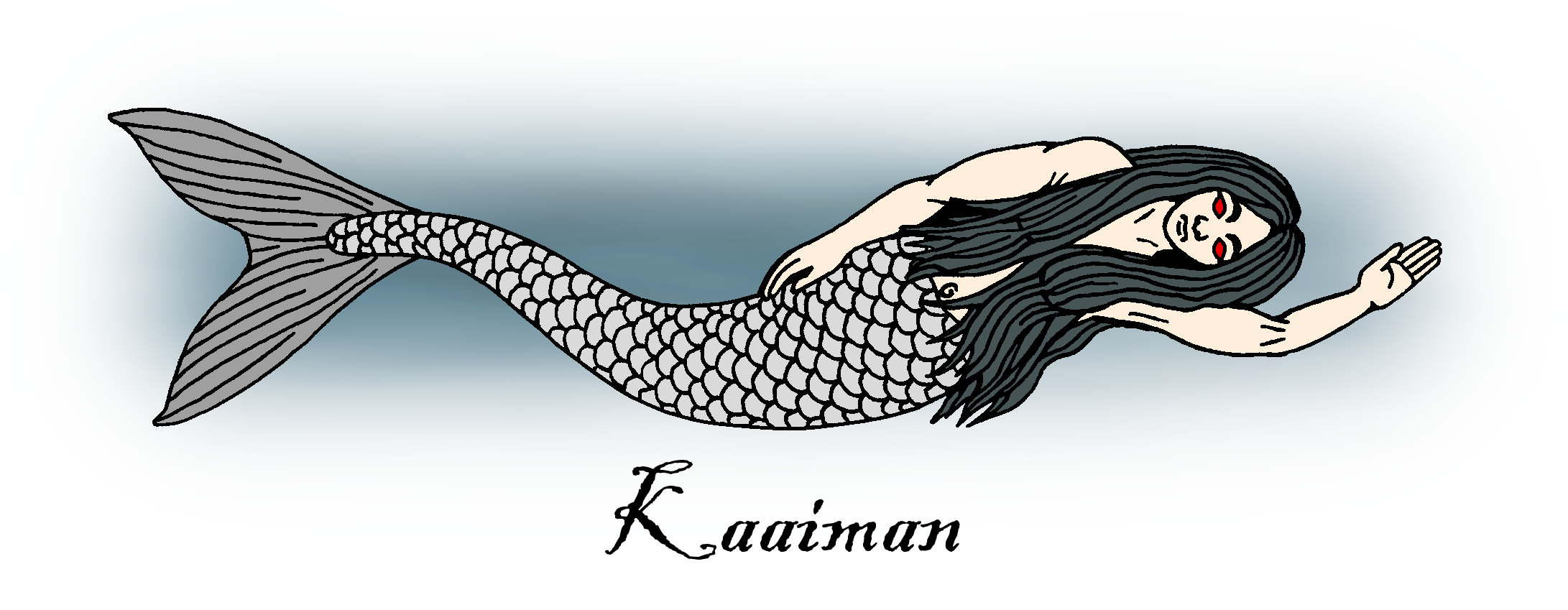

Believe it or not, in certain regions of the world sightings of and belief in merbeings have persisted right up to the present day. In 1947, an elderly Hebridean fisherman reported sighting a mermaid combing her hair near the shore of the Isle of Muck (Matthews & Matthews, 2005). In June 1967, passengers aboard a ferry travelling past Mayne Island, British Columbia, observed (and one snapped a photograph of) a blonde-haired dimple-faced mermaid with the tail of a fish or porpoise sitting upon a shoreside rock (Obee, 2016). In January 2008, several South Africans who had been relaxing near the bank of the Buffelsjags River at Suurbraak claimed they encountered a river-dwelling mermaid with white skin, black hair, and hypnotic red eyes known locally as the Kaaiman (Pekeur, 2008). In 2009, dozens of eyewitnesses caught sight of a mermaid porpoising and performing aerial acrobatics off the beach of Kiryat Yam, Israel (“Is a Mermaid”, 2009). As recently as 2012, workers at a dam in northern Zimbabwe insisted that mermaids were to blame for mysterious malfunctions and refused to continue their work until the harassing entities were appeased with a traditional beer ritual (Conway-Smith, 2012).

Merfolk number among the most widespread of legendary beings. Diverse cultures around the world have told stories of aquatic humanoid beings with piscine tails. Tales handed down from generation to generation attest to mankind’s relations with merfolk, for good or ill, throughout the ages. Perhaps such lore is merely the product of human imagination, but what are we to make of reports of actual sightings? Historic and more recent claims of seeing mermaids or mermen could be chalked up to mirages, misidentifications, hoaxes, or even mass hysteria. For instance, Columbus might have spied a trio of manatees. Witnesses who saw a mermaid on Mayne Island may have actually seen a human girl posing with a fake mermaid’s tail. Men who refused to continue work on a dam in Zimbabwe due to interference from mermaids might have fallen victim to mass hysteria. Whatever the truth of the matter, belief in merfolk has endured over time and continues to endure, in some locales, to this day. Regardless of the reality, merfolk continue to have a place in the hearts, minds, and imaginations of their land-dwelling mortal counterparts.

References

Briggs, K. (1978). The vanishing people: fairy lore and legend. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Briggs, K. (1979). Abbey lubbers, banshees, and boggarts: an illustrated encyclopedia of fairies. New York, NY: Pantheon Book.

Cohen. D. (1982). The encyclopedia of monsters. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead & Company.

Conway-Smith, E. (2012, February 12). Zimbabwe mermaids appeased by traditional beer ritual. PRI. Retrieved from https://www.pri.org

Croker, T. C. (1882/2008). Irish fairy legends. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

DocumentaryMakedonia. (2013. May 24). The legend of Thessalonike, a mermaid who lived in the Aegean sea [. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pHSOjYTco0U

Franklin, A. (2002). The illustrated encyclopedia of fairies. London, England: Collins & Brown.

Is a mermaid living under the sea in northern Israel? (2009, August 12). Haaretz. Retrieved from https://www.haaretz.com.

Marriott, S. (2006). The ultimate fairies handbook. London, England: Octopus Publishing Group.

Matthews, J., & Matthews, C. (2005). The element encyclopedia of magical creatures. London, England: HarperElement.

Munro, A. (2016, March 16, updated March 17). The myth of the Hebridean mermaid. The Scotsman. Retrieved from https://www.scotsman.com

Obee, D. (2016, January 8). Dave Obee: mermaid had no legs, but story does. Times Colonist. Retrieved from https://www.timescolonist.com/

Ó hÓgáin, D. (2006). The lore of Ireland: An encyclopaedia of myth, legend and romance. Woodbridge, England: The Boydell Press.

Pekeur, A. (2008, January 16). Mysterious ‘mermaid’ rises from the river. IOL. Retrieved from https://www.iol.co.za.

Rose, C. (1996). Spirits, fairies, leprechauns, and goblins: an encyclopedia. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Rose, C. (2000). Giants, monsters, and dragons: an encyclopedia of folklore, legend, and myth. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Rosen, B. (2008). The mythical creatures bible. London, England: Octopus Publishing Group.

Salaperäinen, O. (2016). A field guide to fantastical beasts. New York, NY: Metro Books.

Simpson, J. (1987). European mythology (library of the world’s myths and legends). New York, NY: Peter Bedrick Books.

Sykes, E., & Kendall, A. (1952/1993). Who’s who in non-classical mythology (Rev. Ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Towrie, S. (n.d.). Monsters of the deep: mermaid accounts and sightings. In Orkneyjar: The Heritage of the Orkney Islands. Retrieved from http://www.orkneyjar.com/folklore/mermaids.htm

![]()