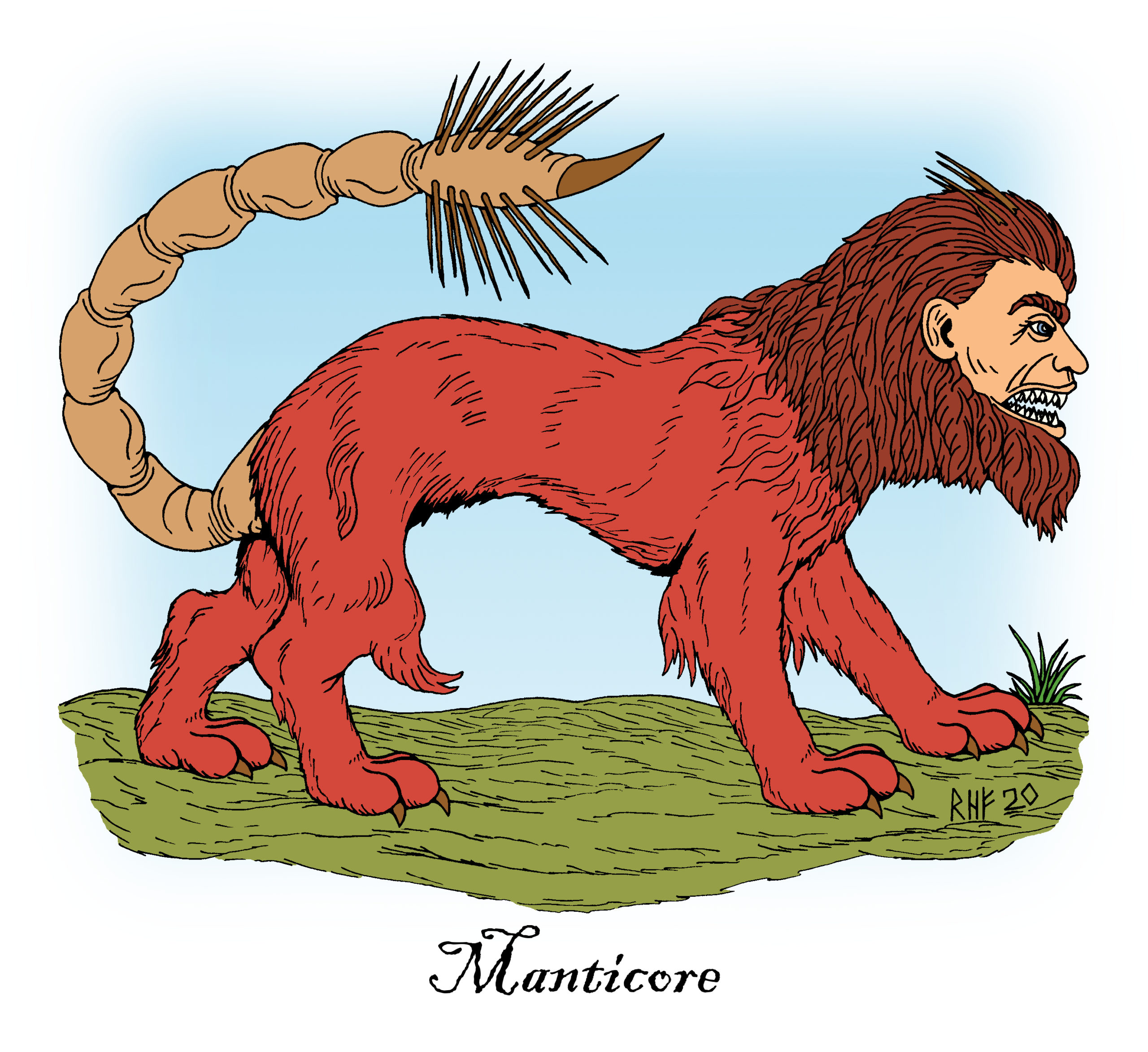

Manticore: Man-Eating Hybrid Beast of Legend and Art

Richard H. Fay

A legendary monster that bore many names (Manticore, Manticora, Mantichora, Manticory, Manticoras, Martikhora, Mantiserra, Memecoleous, Mancomorion, and the Satyral), the fearsome Manticore featured in the lore, bestiaries, and creative works of various lands and cultures, from ancient Asia to medieval Europe, and beyond. However, the Manticore legend first took root in ancient Greece and Persia. A garbled account of man-eating Bengal tigers of India may have been the seed that sprouted all subsequent tales of this strange and ferocious hybrid creature. Despite its dubious origins, the legend of the Manticore persisted and developed over the centuries.

Ctesias, Greek physician to the Persian King Artaxerxes II Mnemon (reigned 404 to 358 BCE), penned what seems to be the first written account of the Manticore. Even though Ctesias never visited India, he wrote that a lion-sized man-faced monstrosity prowled the sub-continent. As preserved in later works by the Roman writer Aelian (c. 170 – c. 235 CE) and the Byzantine scholar Photius (c. 815-897 CE), Ctesias described what he called the Martikhora (derived from the Persian mardkhor, meaning “man-slayer” or “man-eater”) as possessing pale blue eyes, three rows of sharp teeth, savage claws, a cinnabar-coloured pelt, a scorpion’s tail, additional stings on the crown of its head and each side of its tail, and a voice that sounded like a trumpet. Ctesias also claimed that the creature could, to defend itself, shoot regenerating foot-long stingers both forward and backward a considerable distance. One animal alone could withstand those poisoned quills; the thick-skinned elephant had little to fear from the Manticore’s otherwise deadly sting. To hunt such a formidable beast, Indian natives rode upon elephants and attacked their prey with spears or arrows.

It seems likely that the man-eating Martikhora of Ctesias was based upon tales of the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris). The Romanised Greek Pausanias (c. 110 – c. 180 CE) believed this to be the case, and wrote about his thoughts on the matter in the ninth book of his ten-volume travelogue entitled Description of Greece. In his section on fabulous animals, he suggested that the red-hued pelt described by Ctesias could be explained by a tiger appearing to be a homogeneous red in colour when observed running in full sunlight. Pausanias also put forward the opinion that the more fanciful traits recorded by Ctesias, such as the lethal stingers and three rows of teeth, arose from natives exaggerating the deadly characteristics of a man-eating beast they dreaded. According to what Irish naturalist Valentine Ball wrote in his 1883 paper “Identification of the Pygmies, the Martikhora, the Griffin, and the Dikarion of Ktesias”, these two traits dismissed by Pausanias as false may have had a basis in fact. Ball argued that the Manticore’s three rows of teeth might have been derived from the tiger’s trilobate molars, while the tail-borne stingers might have been a distorted account of a horny dermal structure he asserted exists at the extremity of a tiger’s tail.

Regardless of the reality behind Ctesias’ account, other ancient writers helped propagate the legend of the Manticore. With the sceptical qualifier of “if we are to believe Ctesias”, Aristotle described the Martichora of India in his History of Animals of 350 BCE. He included most of the characteristics already mentioned and also said that the beast’s call sounded like a combination of pan-pipes and a trumpet. The Roman author and naturalist Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia of c. 77 CE, displayed little scepticism over the creature’s actual existence when he echoed Ctesias and Aristotle, although he placed the creature in Ethiopia. He added that the triple-rowed teeth fit into each other like a comb. He also claimed to have been informed that the man-faced monster could mimic human speech.

Inspired by the writings of ancient Greek and Roman naturalists, the compilers of medieval bestiaries included the Manticore among their compendia of beasts, both ordinary and fantastic. The exact appearance of the creature varied from work-to-work, although all variations displayed a feline-body with a human face. One 12th century bestiary featured a Manticore wearing a Phyrgian cap. An English bestiary of the early 13th century portrayed its Manticore as possessing a particularly savage countenance and prominent stingers all along its tail. Another mid-late 13th century English bestiary depicted the Manticore with a visage that was merely a rough approximation of a human face. Yet another 13th century bestiary, this one from northern France, portrayed the beast as having a distinctively human head, but no stinging tail. This particular depiction also deviated from the standard reddish coat colour, in this instance (assuming the colour hadn’t faded or altered drastically over time) the illuminator had instead opted for a greyish hue.

Besides its frequent presence in bestiaries, the Manticore also made appearances in medieval sculpture and even, on rare occasions, medieval and Tudor heraldry. The Manticore carvings found in some medieval churches stood as symbols of the weeping prophet Jeremiah. The late medieval Lord Hastings adopted a tusked Manticore (or mantyger) as his heraldic badge. The Tudor-era Lord Fitzwalter had, for his badge, a purple-hued Manticore. At times, the head of the heraldic Manticore would be adorned with spiral horns.

Over time, the Manticore became associated with other fabulous creatures and served as inspiration for other legendary monsters. In the later Middle Ages and Renaissance, the heraldic Manticore helped shape the imagery of the female-faced chimaeric creature that stood as a symbol of the sin of fraud in “grotteschi” (grotesque decorative elements) and some Mannerist paintings. Edward Topsell, in his 1607 work The Historie of Foure-Footed Beastes, copied the description of a Manticore as given by Ctesias, but then equated the man-faced beast with the badger-headed cloven-hoofed Leucrocota and the hyena. In Spanish lore, the Manticore transformed into a kind of werewolf that kidnapped and preyed upon children. Tales of the Manticore told by sixteenth century missionaries to the New World may have formed the basis for the Cigouave, a human-faced feline-bodied beast, of Haitian Vodou tradition.

As the ages progressed, the Manticore of art and popular culture gained additional attributes. Along with the spiral horns added by heraldic artists, others tacked on scales, udders or dragon’s wings. A scaly Manticore sporting horns, udders, and wings featured in a 17th century bestiary. In modern times, a bat-winged Manticore has numbered among the monsters that adventuring characters may encounter in the fantasy realms of a certain well-known role-playing game. The Manticore in Gustave Flaubert’s 1874 work The Temptation of St. Anthony spoke of possessing screw-like claws and the ability to spew plague.

Interestingly enough, although it seems likely that distorted tales of man-eating tigers served as the basis for the man-faced scorpion-tailed stinger-flinging Manticore of ancient natural histories and medieval bestiaries, the legend lives on. In Indonesia, some villagers today tell tales of a man-eating Manticore that prowls the jungle and kills its human prey with a single bite or scratch. It just goes to show that the Manticore has endured, in human imagination if not necessarily in reality.

Sources

Aelian (1958). On the nature of animals 4.21. (A.F. Scholfield, Trans.). Attalus. (Original work written c. 200 CE) http://www.attalus.org/translate/animals4.html

Aristotle (1910). The history of animals. 2.1. (D. Thompson, Trans.). The Internet Classics Archive. (Original work written 350 BCE) http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/history_anim.2.ii.html

Badke, D. (ed.). (2011, January 15). Manticore: gallery. The medieval bestiary.

Ball, V. (1883). “Identification of the pygmies, the martikhora, the griffin, and the dikarion of Ktesias”. The Academy, XXIII, 277.

Curran, B. (2016). The carnival of dark dreams. WyrdHarvest Press.

Flaubert, G, (2016). The temptation of St. Anthony. (L. Hearn, Trans.). (Original work written 1874).

Gygax, G., & Arneson, D. (1981). Dungeons & Dragons fantasy adventure game expert rulebook. TSR Hobbies.

Heraldic badge of William Lord Hastings [ink drawing]. Wikimedia Commons. (Originally drawn c.1466-70)

Lehner, E. & Lehner, J. (2004). Big book of dragons, monsters, and other mythical creatures. Dover Publications.

Manticore. (2020, March 2). Wikipedia. Retrieved March 3, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manticore

Matthews, J., & Matthews, C. (2005). The element encyclopedia of magical creatures. HarperElement.

Pausanias (2018). Description of Greece (English). 9.21.4-9.21.5. Perseus under PhiloLogic. (Original work written c. 150 CE)

Photius (2017). Photius’ excerpt of Ctesias’ Indica. (J.H. Freese, Trans.). Livius. (Original work written c.850 CE)

Pliny the Elder (1855). The natural history 8.30 & 45. (J. Bostock & H.T. Riley, Trans.). Perseus Digital Library. (Original work written 77 CE).

Rose, C. (2000). Giants, monsters, and dragons: an encyclopedia of folklore, legend, and myth. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rosen, B. (2008). The mythical creatures bible. Octopus Publishing Group.

Rothery, G. (1994). Concise encyclopedia of heraldry. Senate. (Original work published 1915)

Topsell, E. (1607). The historie of foure-footed beastes. Printed by William Iaggard.

Zell-Ravenheart, O., & DeKirk, A. (2007). A wizard’s bestiary. New Page Books.

![]()