Malame, a year past sprouting groin hair, was tall for his age, and thin. Old enough to work the plow horse and tend crops for his family. And to bring a sack of wheat to market to barter for other food. Just after reaching the village commons of Droughne, Guthfried walked up to him and yelled, “Freak, get out of our village!”

Malame reddened and yelled back, “Shut up, you overstuffed pig!”

Guthfried yanked the grain sack off Malame’s shoulder, slit it open and strewed the wheat across the sodden grass.

Malame exploded into jagged hatred. “You bloated pus bag!” he yelled. “You won’t cut anything else.”

Guthfried screamed and dropped his knife, waving his arm. The fat in his hand sprouted flames, splitting his skin and creating a thrashing torch. He screamed for almost a minute before fainting. As other villagers rushed to put out the fire, Malame turned and ran back to the only safe place he knew, their hut.

After reaching home, Malame admitted to his father that the wheat was lost and that Guthfried had been given a charred hand. His father had looked sad rather than angry. “I warned you that if you let this evil out it will be your death?” He sighed. “Stand still, Malame.”

He took a hemp cord, bound Malame’s hands behind him, and hobbled his legs.

“I’m sorry, Malame. If you run away, the villagers will persecute your mother, sister and me. If I turn you over to them, there is a chance that they will allow us to remain here and survive.”

Malame almost never cried, but he did then. “Father, they’ll kill me.”

“Hopefully not. After they have you captured, I’ll talk to the elders.”

Once Guthfried had been treated the villagers clotted up. They agreed that Guthfried deserved to be harmed—he was a bullying thug. But they feared the infernal way Malame had deformed him, and feared whatever else Malame might do to them.

Five villagers armed with axes and knives walked to their croft. Malame’s mother and sister held each other, crying, as he was dragged out. His father watched without tears or expression.

As he was being yanked back to the village, neighbors were waiting along the path and struck him with sticks and thrown rocks. Droughne was too small to have a prison, so Malame was untied and tossed into a log-sided storage hut; the door secured behind him.

Those passing by took the trouble to curse him.

“Die, witch!”

“Demon child, you’ll burn!”

“Rot without a grave, evil one!”

As he tried to sleep, he rolled back and forth, disturbing foraging chiggers and fleas, trying to ignore pains from the bruises the villagers had beaten into him along the way. The next morning his father entered the hut bringing fried fatback and black bread.

“Father.”

“Eat while I talk, they may try to take the food away from you. I’m sorry, Malame, but I warned you. We could hide your nature only if you never showed it. But you kept tormenting the villagers. The elders are insisting that you either be killed or banned, and in order to ban you they demand payment in coin we don’t have.”

Malame sobbed. “I don’t know how it happens father, it just does. It’s something in me that reaches out when I don’t really want it to. I’m sorry for Guthfried, rotten as he is, I shouldn’t have hurt him. But this-thing I have erupts without my wishing it.”

“And might soon kill you as well. I’ll try and come back before you go before the elders.”

Later that day, the village blacksmith entered the hut while two other men stood watch outside the door. He looking more frightened than Malame did as he handed over a greasy stew that reeked of turned meat,

“Slaka, please tell me what’s happening.”

“I’ve been ordered not to talk to you.”

Malame realized that Slaka was afraid of him. “If you tell me what’s happening, nothing bad will happen to you.”

Slaka looked behind himself to make sure the guards were far enough away. Then he whispered, “Guthfried’s family wants you dead. The elders seem to agree, but your father is trying to make a blood payment. There will be an assembly this evening to decide what to do with you. I can’t say anything more.”

Slaka hustled back out of the cabin, securing the door behind him. Malame tried to use the misbegotten power inside himself to undo the door, but failed. It came only as an urge, willed by hate.

Just before sunset, four villagers came in, two holding knives and two with ropes. One villager rebound Malame’s hands while another re-hobbled his feet. Then they lead him out to the village common. There were over a hundred people there, and even some strangers who had paused in their travels to watch what could be an execution.

Malame’s family stood to one side. His father approached him and leaned into his ear. “Beg for mercy, son, offer to work as atonement. We don’t have coin or chattel enough to free you. I’m sorry.” For the first time Malame could remember, his father was silently shedding tears.

“I don’t want to die, father. Will you speak for me?”

“I tried. But these people are a mob that wants you dead.”

The elders beat their staffs against a hollowed-out log, the booms reverberating through the crowd. “Bear Witness. Bear Witness,” the elders chanted. “We are here to scourge a demon and exact retribution. Bear Witness.”

Malame looked out on clustered faces of hate and fear. He saw other boys he had played with but there was no mercy in their expressions, and he knew that he could expect none. As he watched, the crowd began to part from the rear, A gaunt old man, stringy hair down to his shoulder blades, was walking toward him. A preternaturally loud voice emerged from his frame.

“People of Droughne. Elders. Before a decision is rendered, hear my alternative.”

One of the elders motioned to nearby villagers to restrain the gaunt man, but something grim in his appearance made them pause, and he reached the front of the crowd. “There is a choice that punishes this evil doer and rewards the folk who live here.”

The chief elder waved the crowd murmurs into silence. “What is this choice?”

“Sell Malame into slavery serving me. I am the harshest of task masters and will ensure that he suffers enough to wish he were already dead. He will wear my slave collar before we leave the village. And I will provide gold to the village to an equivalent of five silver pieces for each villager, doubling that for each elder.”

The murmurs swelled into a roar. Except for Guthfried and his family, the crowd wanted the coin.

The chief elder stilled the crowd with gestures. “How are you called, stranger?”

“I am known as Isthfrig.”

The old man carried no pouch or sack, not even a staff, and wore what looked like a reptile skin tunic.

“And how, Isthfrig, would you provide this payment?”

The gaunt man reached inside his tunic and pulled out a gold chain half his height. “We will weigh and count the links until there is satisfaction,” he said.

Guthfried meanwhile had pushed his way to the front and waved what was left of his cloth wrapped hand. “And where is the justice for this!” he yelled.

Isthfrig’s glare seemed to crackle the air between the man and boy. “Ah, the wounded bully. Very well, two additional gold links for the toasted fingers.” He continued before Guthfried could yell again. “It would be safest for you to remain silent and nod your head yes.”

Guthfried glared back, but the old man had a palpably menacing presence that kept him silent, and after a few seconds he nodded agreement.

Isthfrig nodded. “Good. I must move on quickly, and we should conclude this now. Do we have agreement?”

The elders huddled together for several minutes, then turned to face the crowd. In a loud voice the chief elder intoned, “Does this proposal have the approval of the village?”

The yelled ‘yesses’ left no doubt.

The chief elder nodded. “We have agreement, Isthfrig.”

The weighing of the gold was conducted in view of the crowd, with eight links changing hands. From another inside pocket Isthfrig took out a shiny neck ring made up of small links, too shiny for silver, made of a metal unknown to the villagers. He locked it on Malame’s neck and stood by as Malame said goodbye to his family. After a few minutes he curtly waved for Malame to follow him up the cart path leading from the village.

As they walked, Malame turned his head toward the Old One. “Thank you for saving me.”

“Do not thank me for slavery. You will soon not thank me at all.”

Relief made Malame babble. “I’m told that our tongue is unknown more than a dozen hills from where we live. How is it that you know it?”

Isthfrig, with snake-speed, slapped Malame full in the face, leaving a welt. “You are a slave, not my conversation partner. You do, immediately, what you are told, and answer only when told to.”

The anger that would have let Malame try to use his curse was stillborn. He sensed that this Old One had power much more intense than his own. He nodded.

Within fifteen minutes’ walk they reached two tethered horses, mounted them, and left. Malame choked back questions about how it was that the horses came there and remained unstolen. The Old One’s slap still stung.

Stars and moon glowered down at them as they moved along the path for another three hours, deep woods on each side. Then they stopped at a clearing. “We make camp now, and move on at dawn. Build a fire and hostel the horses.”

Malame tended to both. When finished he came back to the fire, where Isthfrig was squatting.

“Sit,” the Old One ordered. “You will be punished if I must say something twice, so hear me the first time. However, you know nothing of me and may, on this occasion ask questions.”

“Will this thing inside me kill me?”

“It’s part of your being that you’ve buried. I will nurture this aspect, but as it flourishes, your power will either quickly improve or cause your death.”

“But it’s a curse I want to get rid of.”

“But never will, it is your essence.” Isthfrig said. He continued, “You will remain my slave for two years, during which time you will come to hate me. You will also come to learn some little of my ways. At the end of the years if you have survived, you will be given a choice. Either to be freed and perhaps resume foraging for food as a farmer, or to be bound into my path. If you remain with me your gift will blossom into something wonderfully monstrous and will make you more and less than human. Have your shit-stuffed village ears comprehended any of this?”

As Isthfrig had been speaking, Malame’s gut registered that he wasn’t going to be executed that night, “Thank you, great Isth… ah should I call you Master?”

The Old One snorted. “It will do. Have you understood?”

“I believe so, Master. I’m a good farmer and can tend your crops and stock.”

“I have others who already do that. You are to learn what I teach you, observe what I do and replicate it, observe how I act and emulate it. I will be harshly testing you from this moment forward. Know that it is only by courting death that you can attain this life.”

Isthfrig waved his hand toward the saddles. “There is a skinning knife in the pouch on your saddle. Fetch it and keep it as close as your mother’s blessing.”

Malame did so, lay down across the fire from the Old One, and went to sleep. In the dark second half of the night, he woke to hoarse, rasping breathing. A large black shape was creeping toward him, not two man-lengths away. He clasped the knife and went onto his knees just as the wolf leaped. Malame swung his left forearm into the side of the wolf’s head, dodging its teeth, and sliced the knife into the wolf’s hind quarter as it passed over him.

The wolf thudded to the ground and slewed around to reattack. But Malame’s cut had severed a tendon, and the wolf’s left rear leg dangled uselessly. Despite that, it quick-limped toward him, jaws open, snarling.

Malame crouched, grabbed a fist sized stone, and slammed it into the wolf’s head. The wolf dropped and Malame jumped to its side and stabbed into its chest. The wolf’s howl sprayed blood. It dropped, gasping hoarsely, beginning to die.

Across the dying embers of the fire the Old One sat watching. “Finish him, Malame, he deserves a clean death.”

Malame’s suspicions were aroused. “You somehow ordered it to attack me, didn’t you?”

“He’s an aged outlier, a lone wolf no longer able to catch and kill prey. I gave him a fighter’s chance to live another day. Much the same as I give you. Had he killed you I would have let him feed on you. Tomorrow morning cut out his back strap and we will eat it for breakfast. It is what he would want.”

Malame looked into the wolf’s rheumy eyes. “Forgive me,” he whispered and cut across its throat. He turned back to Isthfrig. “Why would you chance having me killed when you just paid so much to rescue me?”

The Old One’s expression could not be read. “You have no idea what you are capable of, of what you can become. With each trial, if you are not dead, you will progress, until your worth to me will be immensely more than a few gold links. To survive you must stop trying to suppress your gift and instead embrace it. Here is your first spell- opheroe mobarae nictatae. Repeat it to me.”

“Opheroe mobarae nictatae.”

“Repeat this a hundred times on bedding down and again on awakening. It pries opens a passageway to what you are. But say it only to yourself, not aloud.”

“Why not aloud, master?”

“Because idiot, it might allow other, unwanted things to conjoin with you. And this is your last painless warning, do not question my instructions. Just do.”

Malame replenished the fire and lay down next to it, silently repeating the charm. He woke when first light sliced through a break in the trees, wondering why he wasn’t hearing the clucks and bellows of farm animals and the stirrings of his family. Then he remembered where he was, without family and friends, and sorrow welled up. He also remembered the Old One’s instruction and repeated the charm to himself.

As he finished, he felt something just outside his grasp, something sinewy and potent.

“Good,” Isthfrig said. “It begins. Try not to die before the transformation. And get to work.”

Malame rekindled the fire and cut open the wolf, waving off the flies. He stripped out the back strap and skewered it for cooking.

“Leave the carcass,” the Old One said. “We’ll give the crows easier pickings. And don’t overcook the meat, it’s already tough.”

Once having eaten, the two broke camp, remounted and left. As they rode the horses at a walk Isthfrig continued Malame’s instruction. “Don’t try and remove the collar, it would kill you. And it serves as a beacon so I can find you, for you indubitably will get into trouble. As you develop your presence, I will begin to teach you rudimentary magics.”

“Are you a magician, Master? A sorcerer?”

The Old One actually smiled. “Of a kind you cannot yet conceive of. Ahead, four hours ride away, is another village. Repeat to yourself so often that it belongs to you, ‘Cocare Nulthrag. Cocare Nulthrag.’ You must be ready to say it aloud when I command you.”

Malame opened his mouth to ask why and then jailed the question. The old one did not like questions. “As you order, Master.”

“Swing your horse next to mine.”

Malame did so, and the Old One reached over, pushed his index finger against Malame’s forehead and held it there. Malame felt a roaring in his head like a river in flood, ripping away years of repression and denial. He felt, for the first time since he could speak and had to hold his tongue, what he innately was. He gasped and almost fell out of the saddle.

“Master, what?”

“Ask no more questions, you won’t yet understand the answers. I need to funnel goetic power through you to cleanse you out. To achieve this, I will spell some of the villagers, using you as the conduit. You will need to look serious and wise, and not like the callow boy you are. Before you feel the spell pass through you, repeat the words I gave you.”

“Cocare Nulthrag.”

“Just so.”

They rode until the sun was overhead, approaching the village from downwind, and smelled a mixture of excrement, decaying animal tissue and wood smoke just before they saw it. The rank aromas were familiar and reassuring to Malame.

There were few villagers out in the midday heat as Isthfrig and Malame plodded up the guttered dirt road toward the village center, and those few stared with hooded eyes. Strangers most often meant trouble.

Once they reached the center of the village, Isthfrig stopped a passerby. “We are healers, willing to provide cure before asking payment. Where can we find the village headman so that we can demonstrate the truth of what I say?”

The man studied Isthfrig and his chela, saw no weapons, and pointed to a large hut on a knoll at the edge of the common. “Flouth is in there, no doubt taking a nap after having worked hard at nothing. He won’t be happy if you wake him.”

Isthfrig woke him. “Most esteemed Flouth, I am advisor to the healer, Malame, who stands before you, come to cure your villagers of various ailments.”

Flouth yawned, releasing breath decayed by the residue of many meals. “Leave immediately, before I have you both trussed and flogged.”

“Please, hear my suggestion. In return for your sanctioning his cures, we would provide you with one tenth of what your village folk kindly donated.”

Flouth’s eyes widened. “Just another ruse to sell poisons as medicines. Why should I lose respect to gain a few coins?”

The Old One glanced at Malame. “You were right, beloved seer, he does suffer greatly from soreness in his toes and finger joints. Should we not cure him as demonstration?”

Malame had to clinch his jaw to keep it from dropping open. “Ah, yes, we should.”

Isthfrig held up a finger to stop Flouth from objecting. “Please dear one, heal him.” Then he glared at Malame.

“What? Oh yes, Cocare Nulthrag.”

Malame felt his mind swirl, then project like vomit into the fat village leader. Malame almost dropped from giddiness. Isthfrig poked him.

Flouth felt his knuckles, then looked down at his feet. “By the sacred gods, I don’t hurt anymore and you haven’t even touched me.”

The deal was quickly struck, with Flouth insisting on twenty percent rather than ten. He assembled the villagers, and praised Malame’s skill.

Isthfrig spoke after him. “We know you have been cheated before by charlatans, and we will not receive payment unless you are cured, and will accept only what you are able to pay. However, be forewarned that an insulting pittance is apt to lead to a short-lived cure.”

The Old One leaned into Malame as though Malame were whispering to him. “Ah, yes. You, in the blue, madam. You have a boil between your breasts that no treatment has removed. Please, step forward. There is no need to disrobe, it is a simple spell. Malame, please help her.”

The blushing woman at first stepped back, but her husband led her forward.

Malame had braced himself. “Cocare Nulthrag,” he whispered hoarsely. As the goetic energy roared into and out of him he stood with only a quaver.

Isthfrig nodded. “Please, feel your chest, madam. Is the boil missing?”

She gingerly touched her breast bone, then rubbed the area. “It’s gone. Thank the gods, it’s gone.”

Her husband gratefully laid five silver coins into an alms bowl. Other villagers crowded forward, and Malame served as the chalice for their spells until he almost dropped from exhaustion and dizziness. He felt at once ravenous and powerful, his being hollowed out and needing fulfillment. Isthfrig helped him as they returned to Flouth’s hut where the proceeds were divided.

“Again,” Flouth demanded, “you must do this again tomorrow.”

Malame started to protest and Isthfrig waved him into silence. “Of course, esteemed Flouth, if that is your wish.”

They were given an abandoned hut to overnight in, and after entering it Malame dropped onto a hay pile without even thinking of food. But the Old One nudged him.

“Eat. Malnourishment will deform you.”

“Master, what have you done to me? A flame burns inside my empty being that wishes to rage.”

“Just so. Sleep now, we will use the depth of the night to leave.”

“Why, if coin is our purpose?”

“Cretin, our purpose was to cleanse you. We’re not gods who work miracles, we make magic. What I did with you could have made their changes permanent, but I decided to let the effects gradually wear off, leaving all as before. The villagers will not be happy with their headman.”

Malame looked at the pile of coins, more than his family would earn in many years. “What will you do with this silver?”

“Keep some if you wish, put the rest in your saddlebag. We may find a use for it.”

Isthfrig brushed his hands together, as if removing soil. “Pandering to these foibles of men is repugnant. Try not to die, I have no wish to do that again.”

“Master?”

“I had to enter into them to determine their ailments and provide palliatives. Almost all of them are cesspools. If you think of the task you most despise you will have a faint idea of my reaction. Oh, and cast Cocare Nulthrag from your mind.”

Malame stared.

“It’s nonsense syllables. I just needed you to say something innocuous while supposedly performing miracles.”

They traveled on for fifteen days before reaching the Old One’s settlement. Along the way he pointed out plants, beneficial and poisonous, and described their uses. Malame was illiterate, and each evening, before the light failed, the old one would teach Malame characters and the words they represented. Malame had a quick mind and remarkable memory, so by the time they reached the camp he could sign his name and write a few simple sentences.

When they reached the camp, they were met by three dozen of villagers, all of whom prostrated themselves as Isthfrig passed.

“Master, may I ask a question?”

“If you must.”

“None of those meeting us wear slave collars.”

“None of them need to. They provide me with food and early warning of visitors, I keep marauders well away, killing those that get too close, and cure ailments.”

“Oh. May I ask one more question?”

“You impose on me at your peril, but yes once more.”

“How did you know where to find me?”

The Old One’s mouth tightened. “You are not unique, Malame. But most of us are killed as soon as we display our gifts, often before we are weaned. We few who survive repress our talents, but even then, are almost all killed before sexual awakening. I pay travelers for information about abnormal youths, and when warranted pay a visit. You are my first visit in over ten years.”

Malame badly wanted to ask how old he actually was, but knew he had exhausted his chance for questions. “Please tell me what I am to do, Master.”

“Become much more dangerous than you are now. And much less gullible.”

Malame’s mornings were spent in weapons training with Oulthag, a survivor of the combat pits, and his afternoons with the Old One, who taught him at first rudimentary and then more sophisticated spells. He became wiry rather than thin, with sharply defined muscles. Once he was adequately literate, he spent the fading evening light reading goetic texts. The hole carved out for him by Isthfrig began to gradually fill.

The Old One needed no help, but Malame began traveling with him, a schooled witness to his master’s magic and ability to deceive. As he became more adept, he began rendering the more mundane curses and cures. Isthfrig infrequently killed and Malame suspected his master thought such killings were sloppy or inefficient. When the Old One did slay someone, Malame was not outraged. Death was a companion who slept beside him.

As his gift swelled, a coldness seeped in. Malame sensed he was no longer completely a man, nor bound by man’s morals. His allegiance was with Isthfrig. He had killed in defense of his master and would, he knew, kill again for him.

Toward the end of his two years, Isthfrig summoned him to his yurt. He sat on the dirt floor casting runes.

“Master?”

“You are to kill a visitor using the magics I have taught you.”

Malame was expressionless, but knew the Old One sensed his hesitation. “What has he done?”

“Not of your concern. The arrival is in seven days. You have my permission to conscript the villagers for your preparations. The visitor is an adept, so prepare for goetic conflict.”

Malame felt a twinge of doubt, but held himself expressionless. “Is negotiation an option?”

“No, although that may be a ploy.”

Malame hesitated. “Would it serve your purpose to just maim him?”

Isthfrig’s look held Malame silent. “How you kill is at your discretion, but if you fail, you will be the one to die.”

The Old One wordlessly tossed rune stones as Malame thought.

“As you wish, Master.” Malame returned to his tent and knelt, drawing symbols in the dirt.

Seven days later, at first light, the villagers alerted Malame that something approached. He in turn told the Old One, who took position at one end of the clearing. Malame stood at the center, between the Old One and whoever would approach.

The gaunt corpse of a young woman entered, alone, hair disheveled, oozing greenly from cuts and sores.

“Move aside or die, slave.”

The words came not from rotted vocal cords but from somewhere within her.

“Halt for parlay.”

As she took several steps toward him, coldness flushed away his doubt. Malame became a honed knife. He weaved his hands in spell, but the creature raspingly laughed. “Your spell affects the living, and I am of the dead. First, I will enjoy your agony, then that of your master.”

Malame threw a spear at the decomposing woman, but it merely passed through her gaping flesh and fell to the ground behind her. “Stupid.” As she raised bony hands to spellcast, Malame quickly gestured.

The ground beneath the woman’s feet tore open into a crevasse twice the length of a man. The corpse fell in and screechingly keened. “The burning!” Then there was silence.

The Old One had not moved or spoken. “Adequately done, Malame. I smell the blending of the noble acids that dissolve even gold.”

“And dissolves even her bones. Evil without substance will not harm us.” He stared at the Old One. “Was she of your creation?”

“No, a former lover and I amuse ourselves by trying to kill each other. You will now have come to her attention.” Isthfrig paused. “We will talk later today about your decision.”

“Decision?”

“To abide or leave.”

That evening Isthfrig and Malame ate rodent stew next to the cooking fire, staring at each other silently as daylight shriveled and the fire darkened to embers. Isthfrig spoke.

“If you leave now, you might be able to earn a living as a hedge wizard. But you will not progress and will perhaps regret that the hole in your being could have been filled with wonders. I will always be curt and abusive, but will also teach you magics that will let you blossom like a night flower. Know that with greater development and awareness comes greater risk. The decision is yours.”

The Old One gestured, and the shining collar unlocked and fell to the ground. Malame rubbed his neck, then half-smiled. “We’re sitting on dirt eating wood rat. It’s indeed paradise.”

Isthfrig bristled, then subsided. “You already know that we do this to maintain focus. Just as you already sense that what you could become will yield delights far beyond the milk of the poppy.”

Malame nodded. “You’ve brined me into something long past redemption, and even if I could be redeemed, I have no wish to.”

Isthfrig inclined his head. “So be it. Open yourself and prepare. The spoken words we have been using for spells are only the echoes of their power. I admit you now to the first room. Learn its doorway so you can return on your own. And trust no promise until after you have tested it.”

Malame lurched without moving into a monstrously huge chamber so tall he could only vaguely discern a ceiling. The old one he knew without seeing was at his side. From the chamber walls, beings and spells billowed toward him almost greedily.

Meanwhile, the bodies of the two magi remained motionless on the dirt. Small insects scuttled toward them, then veered off in fear.

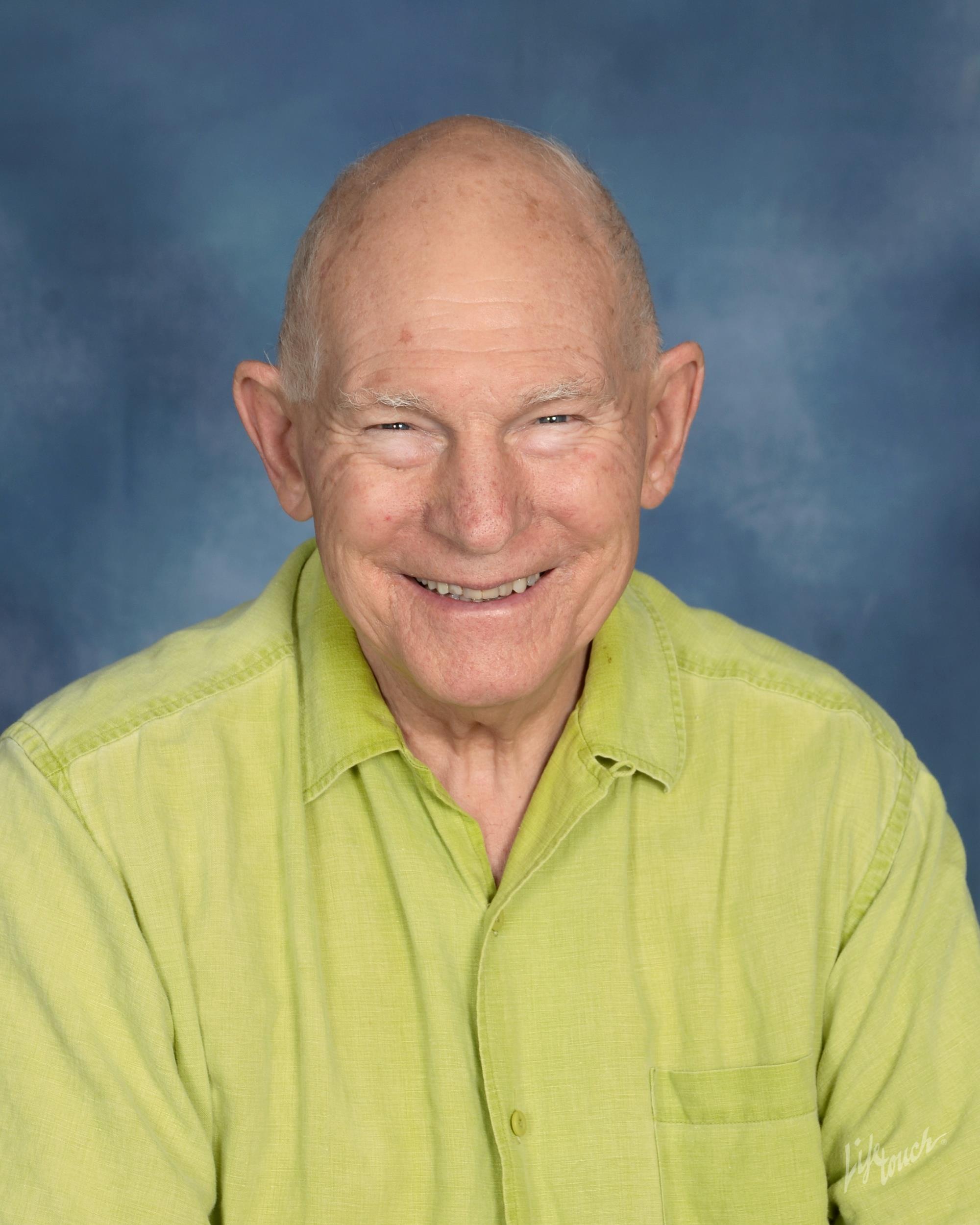

About the Author

Ed Ahern resumed writing after forty odd years in foreign intelligence and international sales. He’s had over four hundred fifty stories and poems published so far, and seven books. Ed works the other side of writing at Bewildering Stories, where he sits on the review board and manages a posse of eight review editors.

Ed Ahern resumed writing after forty odd years in foreign intelligence and international sales. He’s had over four hundred fifty stories and poems published so far, and seven books. Ed works the other side of writing at Bewildering Stories, where he sits on the review board and manages a posse of eight review editors.

Find him at:

https://twitter.com/bottomstripper https://www.facebook.com/EdAhern73 https://www.instagram.com/edwardahern1860/

![]()